| Translate This News In |

|---|

Thursday, in an epic quest to bring back rocks that could answer if Mars had ever been alive, a NASA rover streaked through the orange Martian sky and landed on the planet, taking the most dangerous step yet.

At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of the Space Agency in Pasadena, California, ground controllers leaped to their feet, thrust their arms into the air, and cheered in both triumph and relief upon receiving confirmation that the six-wheeled Perseverance had touched the red planet, long a deathtrap for incoming spacecraft.

“Now the amazing science begins,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s science mission chief, said jubilantly at a news conference where, in the event of a failure, he theatrically tore up the contingency plan and threw the document over his shoulders.

The landing marks the third visit in a little over a week to Mars. On successive days in the past week, two spacecraft from the United Arab Emirates and China swung into orbit around Mars. In July, all three missions took off to take advantage of the close alignment of Earth and Mars, travelling approximately 300 million miles in almost seven months.

At Jezero Crater, the car-size, plutonium-powered vehicle hit NASA’s smallest and most tricky target yet: a 5-by-4-mile strip on an ancient river delta full of pits, cliffs, and rocks. Scientists believe that if life had ever flourished on Mars when water was still flowing on the planet, it would have occurred 3 billion to 4 billion years ago.

Percy, as it is nicknamed, will use its 7-foot (2-meter) arm over the next two years to drill down and gather rock samples containing possible signs of past microscopic life. Three to four dozen samples of the chalk size will be sealed in tubes and set aside to be eventually recovered by another rover and taken home by another rocket ship.

As early as 2031, the objective is to get them back to Earth.

One of the central questions of theology, philosophy, and exploration of space is what scientists hope to answer.

China’s spacecraft includes a smaller rover that, if it safely makes it down from orbit in May or June, will also seek evidence of life. Two older NASA landers on Mars are still humming along: the Curiosity Rover 2012 and the InSight 2018.

During its descent, perseverance was on its own, a manoeuvre often described by NASA as’ seven minutes of terror.’

As the pre-programmed spacecraft hit the thin Martian atmosphere at 12,100 mph (19,500 kph), or 16 times the speed of sound, slowing as it plummeted, flight controllers waited helplessly. It released its 70-foot (21 metre) parachute and then used a rocket-steered platform known as a sky crane for the last 60 or so feet to lower the rover to the surface (18 metres).

It took a nail-biting 11 1/2 minutes for the signal confirming the landing to reach Earth, setting off back-slapping and fist-bumping among flight controllers wearing coronavirus masks.

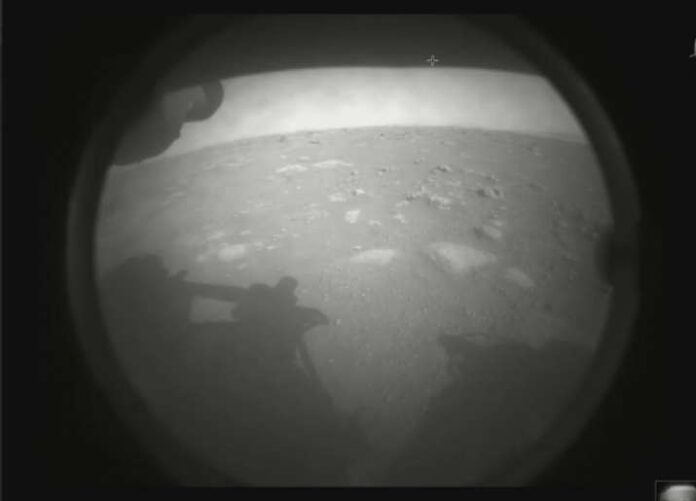

Perseverance promptly sent back two grainy, black-and-white images of the pockmarked, pimply-looking surface of Mars, the shadow of the rover visible in one image frame.

For the world’s spacefaring nations, the U.S. included, Mars has proved a treacherous place. A U.S. spacecraft was destroyed upon entering orbit in the span of less than three months in 1999 because engineers had mixed metric and English units, and an American lander crashed on the surface after its engines were prematurely cut off.

President Joe Biden tweeted congratulations on the landing, saying: “Today it proved once again that nothing is beyond the realm of possibility with the power of science and American ingenuity.”

NASA and the European Space Agency are teaming up to bring the rocks home. The mission of Perseverance alone costs close to $3 billion.

Analyzing the samples in the best laboratories in the world is the only way to confirm or rule out signs of past life. Instruments small enough to be sent to Mars wouldn’t have the precision needed.